Lizard brain, monkey brain, human brain

Hold, Witness, Process, Woo Woo Hats

A boy goes walking with his momma in the woods. He giggles as he explores ravines, jumps on logs and picks up mushrooms. He dances around the laser beams of sunlight cutting through the trees.

A twig snaps, and something scurries across the leaves on the ground. He sprints over to his momma, screaming.

She looks down and says, "It was only a squirrel. Don't be silly, squirrels are harmless!"

She keeps walking. The boy responds by screaming and crying louder.

"It's okay! It's gone now," she says.

More, louder screaming.

Getting frustrated, she says, "In the future, here's what you can do: You can carry a knife so that if something bad really does happen, you'll be ready!"

Screaming.

"Ugh! Will you just calm down? We didn’t come to the woods for you to act like this."

Screaming.

Finally, she picks him up and holds him.

Only THEN does he calm down.

5 seconds later, he yells at her to let him down so he can splash in the puddle up ahead. 😂

When a child is frightened, his instinct to survive isn't soothed when you tell him not to be scared. His emotions don't go away when you rationalize with him.

Why?

Because coping happens in 3 stages—starting with the oldest part of our brains first. Annie Lalla and Eben Pagan taught me this.

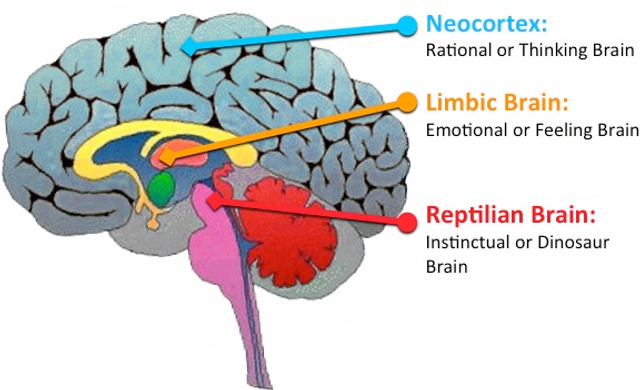

The 3 stages come from the Triune Brain model of development1:

Stage 1: The basal ganglia, aka the “lizard brain.” The basal ganglia is responsible for instinct and survival: fight, flight, freeze, poop, pee, hunger and thirst cues. Those developed early on, back when lizards first came on the scene.

Stage 2: The limbic system, aka “monkey brain.” The limbic system is responsible for our emotions and motivations.

Stage 3: The neocortex, aka “human brain.” The neocortex is responsible for abstractions, language, planning, and perception.

In a conflict or triggering situation, we can’t use our “human brain” until after we’ve soothed our lizard and monkey brains.

We first need to get out of our fight-or-flight response. We do this through physical touch, breathing, and slow, calm speech. This allows us to stop attacking or running away.

When our bodies relax enough to get a deep breath again and our tension comes down, then and only then can we attend to the monkey brain.

Annie says “Our emotions are messengers from our unconscious minds telling us that something is wrong. Every single one serves an important purpose, and their only desires are to feel heard and to be felt.”

When those desires are met, they move through and out of our bodies. Emotions are more subtle than our powerful survival instincts, and we can't hear their whisper until the volume of the instincts is turned down.

Lastly, we can move on to the cutting-edge neocortex. This is where we ponder why something happened in the first place and how we can plan to avoid it in the future.

If we put our woo woo hats on for a moment and imagine that there's a little boy or girl inside every one of us, how do we soothe him or her?

How do you speak to that part of yourself that doesn't feel safe in those moments? Do you allow it? Accept it? Embrace it? Or do you judge it, berate it, and call it names for even existing in you?

One of my 12 favorite problems I revisit often is "How can I best teach my kids to regulate their nervous systems, providing them the safety they need to explore physically and interpersonally?"

One way I embody, or live out, an answer to that question is by regulating myself when they’re freaking out. I remember: When we get angry at a child freaking out, it has nothing to do with them. They can't yet regulate their own nervous system, so they need to plug into mine. They need to feel that I feel safe in order to feel safe. If I get angry, it’s because I’m blaming my kid for my own inability to regulate.

It's noticing the storm inside myself and just letting it be there. And sometimes it’s accepting that I’m dysregulated myself.

P.S. Same goes for all relationships. Hug and hold first, THEN witness their emotions, THEN if there's even a reason to talk about the content at all still, it will be much smoother.

There are newer theories about brain evolution that suggest that emotion and cognition are interdependent. The limbic system doesn’t just do emotions and the cortex doesn’t just do cognition and abstract thinking. With that being said, the triune theory seems extremely useful for practical application.